Extracts from Patrick Kelly’s book ‘Infinite Dao – The Way Opens’ – Chapter 1. (Part 1)

第一章启路1 The Way Opens

初遇大师Meeting the Master

30度的高温下,满怀期望的我在吉隆坡墓园见到了黄性贤大师。选择在这样的地方建立大型培训学校,着实令大师门下的诸多弟子哑然,虽然学校的楼下还开有一间传统的马来中式咖啡屋。黄大师年约67岁,有着普通亚洲人的身高。他胸膛宽阔,犀利的眼神似乎能洞穿一切。一个外国人的突然到访虽令其有些诧异,但他并不动声色。他若一直如此,我也许还有胜算的机会。但此前大师与外国人的接触仅限于几个上了他几堂课的旅行过客的经历,给我的机会蒙上了阴影。出于尊敬,大师还是将我这个访客请进了屋并询问了我的意图。得知我拜师的想法后,一直不动声色的大师这时说:“我不喜欢你的模样,我不会教你。”这一言就道出了大师对我的真实感受,也令在场惶恐的翻译煞是为难。I greeted Master Huang Xingxian with high expectations in the 30 degree heat of the Kuala Lumpur graveyard. That was where, to the consternation of many of his students, he had chosen to establish the large training studio above a typical Malaysian-Chinese coffee house. He was average height for an Asian, barrel chested, around 67 years old with his piercing look giving nothing away. The unexpected appearance of a Westerner on his doorstep almost certainly surprised him, but he did not show it. If he had remained impassive it would perhaps have been more fortunate, but the fact that his previous experience of Westerners was limited to a few transient travellers who had passed casually through his classes before me, precluded that. Ever polite to a guest he invited me inside and inquired what I wished of him, the first indication of his real feelings not appearing until he understood that I hoped to become his student. The nervous translator struggled with Master Huang’s response, “I don’t like the look of you. I don’t intend to teach you.”

The Journey

来此之前,我仔细考虑过此次拜师之行的各种不确定性,比如自己能否在吉隆坡找到住所,资金是否足够,自己是否能找到黄大师,即便找到了,凭那点基础的汉语,自己是否又能听懂并理解大师的所授等等,但我终究还是来了。可我偏偏就没想到,在我卖了房、安顿好生活然后千里迢迢跑到东南亚找到大师时,大师就这么一句话就将我拒于门外。There had been many uncertainties in the planning of this journey, such as whether I could find accommodation in Kuala Lumpur, whether my funds would be sufficient, whether I could even find Master Huang and whether I could understand and appreciate his teaching if I did find him – especially given my rather basic knowledge of the Chinese language. All these practical difficulties had been carefully considered before the journey and I had decided to take my chances with them. However, that he would simply refuse to teach me had not even been vaguely considered when I sold my house, put my outer life in order and set out to South-east Asia to find him.

Genuine Displays

此前我曾跟一位太极导师学了四年。期间,我常听他谈起他和他父亲的师傅黄性贤大师强大的力量及大师对力量的非凡运用。其中令我记忆犹新的,是几年前黄大师与国际著名摔跤手较量的事迹。那名摔跤手比黄大师年轻20岁,体重也重过大师15公斤,他曾多次公开指责太极和黄大师的能力。作为回应,黄大师接受了他的挑战。结果在公开赛上,黄大师将他连摔在地26次,而大师自己一直都站得稳稳当当。如此轻描淡写的胜利,既让人们亲眼目睹了大师的非凡能力,却也让一些后来目睹者心生疑窦,而这样两极分化式的影响在大师今后的生活中还在不断出现。对此,大师的看法是:“太极越是本真和玄妙,理解和相信它的人就会越少。光太极向外界展示出的速度及其戏剧化的动作,都会令人心动。”而我自己后来也有了类似的经历。凭着自身练习与教学的深入,我发现有些人一开始就会努力去了解并最终体验到了太极的价值所在,可也有些人从一开始就对太极抱有一定的抵触态度,之后却在自己的偏差练习和错误理解下,想当然地对太极进行指责。My previous Taiji instructor, in the four years I had known him, had often talked of the remarkable powers and exploits of his and his father’s teacher, Master Huang Xingxian. One memorable example was the story of the Master’s fight with an internationally famous wrestler a few years earlier. The wrestler was 20 years younger and 15 kg heavier. Master Huang – accepting the challenge in response to repeated public denunciations by the wrestler of both Taiji and Master Huang’s abilities – threw the wrestler 26 times over the course of the public bout, never once going down himself. The ease with which Master Huang won, both convinced everybody present of his remarkable abilities, and ironically, aroused doubt within those who only later saw the incredible result. This polarising effect on those around him was to be a recurring story in his life. As he explained later, “The more genuine and subtle the Taiji, the less people understand and believe, but on seeing external, fast, dramatic moves, they are naively impressed.” Later I was to experience this same effect for myself. As my practice and teaching became deeper, people either made an effort to understand, consequently experiencing its value, or from the earliest contact they set part of their mind against the system, then self-righteously criticised it on the basis of their own deviant practice and incorrect understanding.

The Initial Meeting

带着对大师名誉的笃定,面对跟前的大师,我努力“消化”着这突如其来的拒绝,也没想就自己的模样去辩驳。几年后我才明白到,所谓的首访闭门羹,其实是传统上对学员决心的一种测试。对那些还没有对‘铁杵磨成针’做好充分准备之人,导师就不必浪费时间和精力。或许我当时的茫然和长时间的沉默让黄大师认定了我不是那种轻言放弃之人,又或许当时他心底下认为应该再给我一次机会吧,总之好一阵后,大师说道:“先来一个星期吧,每晚5:30到9点上课,观摩一下。” 他还说可以考虑拜师的事。看来这第一步还有收获!带着些许安慰,我谢过大师后离开。初访的经历夹杂有意外,但我与黄大师间的一生深厚关系却由此展开。1992年12月,大师仙逝于中国福州。 Now, standing before him at this initial meeting with his reputation firmly in mind, there was no thought of arguing over my appearance as I struggled to process his unexpected refusal. Years later I understood that this first refusal is a traditional test of the student’s determination to learn. It prevents the teacher wasting time and energy on those unprepared to make the substantial effort necessary to make a success of the training. Perhaps it was my blank stare and what seemed like ages of nothing said as he awaited my response, that convinced him it would not be so easy to send me away, or was it that he experienced some inner-prompting that convinced him to give me a second chance? Either way, after a time he spoke again, “Attend the classes every evening for a week. Watch the practice from 17:30 to 21:00.” Meanwhile, I was told, my request to be taught would be considered. With some relief I expressed my gratitude for the chance and satisfied with this first step, took my leave. That was the unexpected beginning of an intense and close relationship that lasted until Master Huang Xingxian’s death in Fuzhou, China, in December 1992.

Becoming a Disciple

两年后的1979年,在大师位于婆罗洲孤岛的古晋小镇家里,我与师傅的深厚关系经传统的敬茶仪式得到了正式确立。敬过茶,我即视师为父,师傅则视我为子,师傅的个人太极传承自此开启。被收为内校弟子看似荣耀,背后却是大量的勤学苦练。假如师傅在我初访时就告知这背后的艰辛和之后多年我可能会有的经历,我那时未必就能坚持下去。如今几十年过去,那最初的两年恍如一梦。那时的我懵懵懂懂,既没真正意识到自身内在的变化,也没留心那些复杂却又只可意会不可言传的中式礼仪,还有那些让我感觉那样陌生和遥远的中华文化,但我还是将自己的一生交付给了这位在中式文化教育下长大、谜一般却又充满魅力的人。That relationship was formally cemented two years later in 1979 at his home in Kuching, a small town on the isolated island of Borneo, when – after the traditional ceremony in which I presented him with a bowl of tea and accepted the obligation towards him of a son, while he took the responsibility of a father – his personal transmission of the art really began. But that acceptance into his Inner School was an honour which had to be earned. If it had been known at that first meeting, what it would be necessary to go through in those succeeding years, I would have been reluctant to proceed. Now, decades later, those two initial years seem like a dream and that is how I went through them, more or less unconscious of the internal processes being initiated within myself during this time and oblivious to the complicated unspoken Chinese etiquette, placing my life in the hands of this charismatic and enigmatic person, from, what was to me at that time, a strange and distant culture.

The Title Master

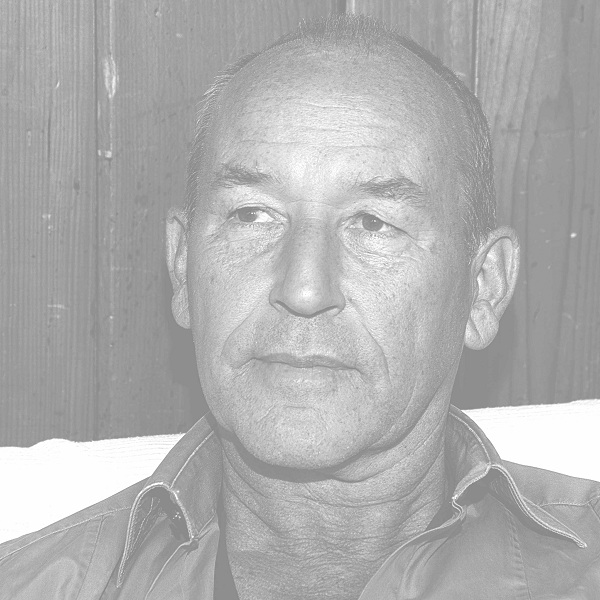

克利 Patrick A Kelly

克利 Patrick A Kelly

began Taiji with an experienced student of Master Huang Xingxian in 1973. In 1977 he moved to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia where he studied full time in Master Huang’s school. In 1979, following tradition, Master Huang accepted Patrick as his personal disciple – the only non-Chinese to ever enter Huang’s inner-school. From that time Patrick Kelly travelled and taught between Asia, Australasia and Europe while continuing to learn personally with Master Huang until his death late 1992. Simultaneously Patrick worked closely both with the Naqshibandi Gnostic Sage Abdullah Dougan for 14 years until Abdullah’s death in 1987 and for 30 years with the Raja Yogi Mounimaharaj of Rajasthan who died in 2007 at more than 105 years old.

1973年,派瑞克利开始向黄性贤大师的一位资深学生学习太极。1977年,他来到马来西亚吉隆坡,在黄性贤大师的学校全日制学习太极。1979年,遵循传统惯例,黄性贤大师收派瑞克利为徒,他成为了黄性贤大师唯一的非华人入室弟子。自那时起,派瑞克利往来于亚洲、澳洲及欧洲教拳,同时继续私下向黄性贤大师学习,直至大师于1992年末去世。同一时期,派瑞克利还跟随纳什般迪派和诺斯替派哲人阿卜杜拉多安学习十四年,直到1987年阿卜杜拉去世,跟随拉贾斯坦的胜王瑜伽大师穆尼玛哈拉吉学习三十余年,直至穆尼大师在2007年以105岁高龄去世。